Choral music from 400 years ago and electronic beats? Stimming relishes the challenge. As a Fellow at Beethovenfest, he is thinking about how he can imbue the mechanical perfection of the synthesizer with a soul – together with the NDR Vokalensemble. Music journalist Patrick Becker asked him about it.

How did the NDR Vokalensemble and you come together?

The NDR Vokalensemble was originally looking for DJs and then approached me. It quickly became clear that I’m not a DJ, but a producer: I produce the individual parts of music to make a finished piece, a DJ puts finished pieces together to make something even bigger. But that means he can’t react to the musicians live at all, he can only choose a few tracks for the ensemble to play over. The first smaller collaborations with parts of the ensemble went so well that we decided to continue working together.

What are the challenges of working together?

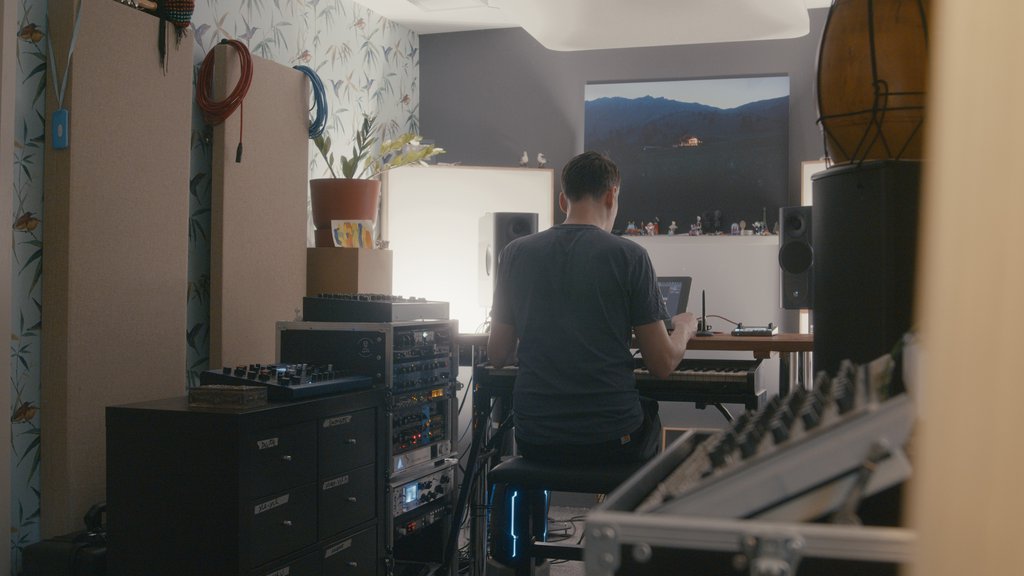

The combination is tricky, especially when the programme consists mainly of classical music. I think that large parts of the audience are real experts in this field and have good speakers or professional headphones at home. Their expectations are very different from those of a young audience that is not so classically inclined. That’s why there are very few people from the techno scene who have ventured into classical music. This challenge has taught me an incredible amount: how important stringency is and how important the stories I want to tell with my music are. I come to the rehearsals with my electronic part almost finished, so that we can work on timing and intonation with the ensemble while I learn where to slow down and where to react to the choir.

How does your artistic approach manifest itself in the music?

I place the choral music and my own contribution on an equal footing. In the end, it should become a choral disc with electronics. Let’s take one of the older pieces in the programme, Sweelinck’s »Miserere«, over 400 years old, based on a simple Gregorian chant: I add a few beats to that, precisely because this composition is so simple that it works well. The piece that gives the concert its name, Janáček's »The Wild Duck«, is so complex in itself that a very soft sound from the synthesiser is sufficient: monophonic and only supporting the choir by using low tones that can no longer be reached by the human voice. I am interested in these contrasts.

What do you hope to achieve for the audience with this form of work?

Without being cheesy: it’s about melodies, about harmonies, about music that can touch. When a moment suddenly comes in a calm musical flow that is deeply moving, it has much more power than if you focus on clichéd emotions all the time. That would wear off very quickly.

The working title of this concert is »Mercy«. What emotional world do you open up with it?

It’s all deadly sad. The conductor, Klaas Stok, and I share a melancholy attitude towards the world. That seemed to us to be the right expression for this concert in order to remain topical. We have the twelfth station from Franz Liszt’s »Via Crucis« composition in the programme, »Jesus dies at the cross«. This is one of the saddest pieces I have ever heard. Even if the idea of »Lord, have mercy« opens up an abstract level, it is intuitively clear which many and complex crises of the present are actually being addressed. This theme also runs through the entire history of the church and is a religious theme in general, which is why there are so many sacred pieces of music about it.

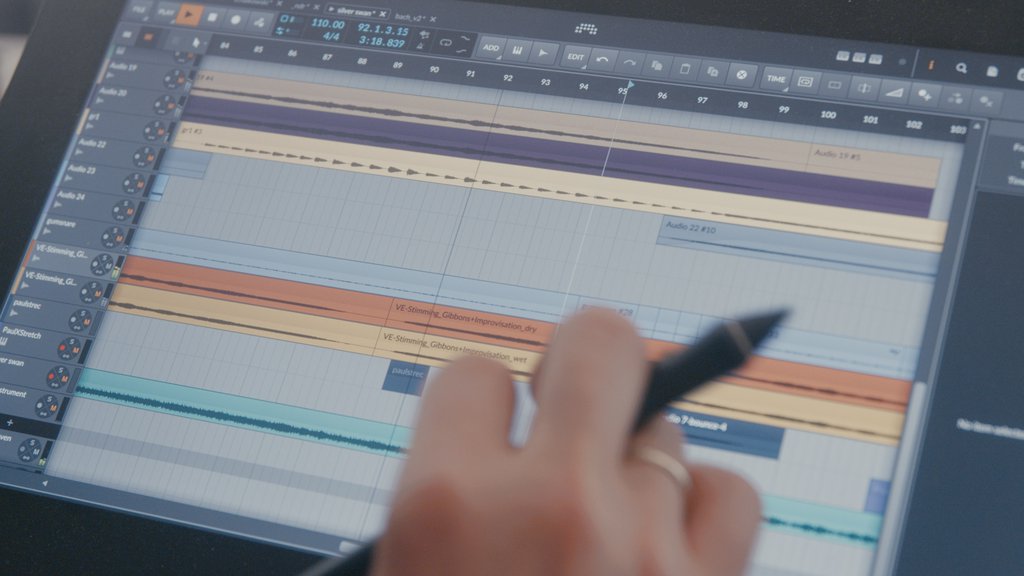

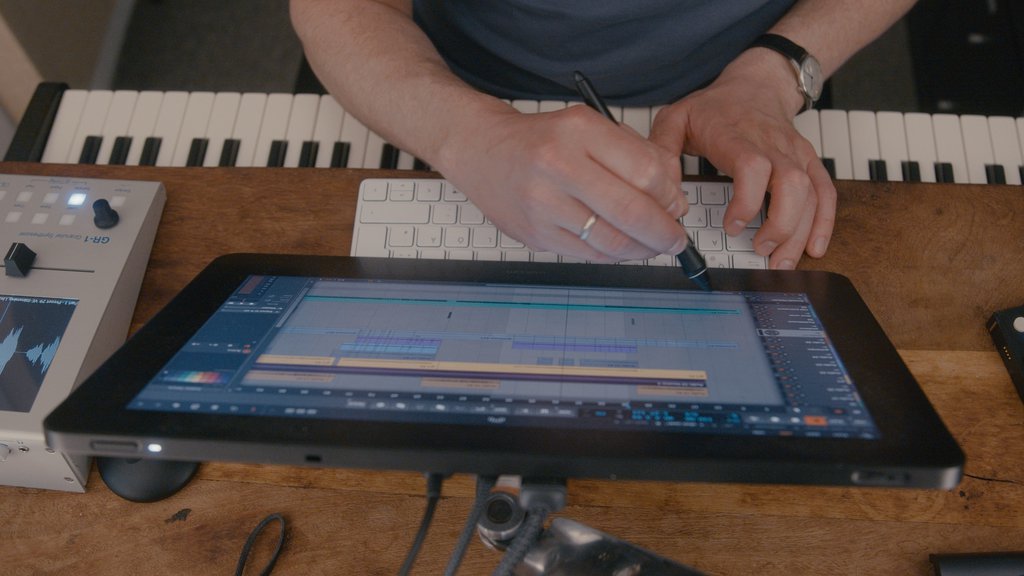

How do you deal with producing such emotional content digitally?

The question for me is always whether it was my intention from the outset to go in a certain emotional direction, whether my devices have a life of their own, so to speak, or whether the mood is inherent in the pieces themselves. I sit down at the machine with an idea that can never be realised: You conceive the actual idea very quickly in a moment, in principle you conceive in half an hour what then takes weeks and months to realise. What always comes to my mind when I work with singers is the actually crazy attempt to breathe life into the computer in digitally generated music – in other words, soul, emotion and also a bit of imprecision. Of course we love to recognise patterns, but we need the imprecision within that pattern to make it interesting for us. Blunt techno is so incredibly boring because there are no imprecisions, because everything is so exact and one hundred per cent mathematically clean. That’s why we meet in the middle: I have to bring imprecision into the computer music and the classical musicians have the challenge of achieving precision from imprecision. This then suddenly creates a moment that has never existed before and is touching in a new way.